The reason my Chinese sounds different from native speakers is because I’m translating my words. I hear a question in Chinese, think of a response in English, convert that to Chinese, and then respond back in Chinese.

It’s … adequate. It gets the message across, we can carry a conversation, but it simply doesn’t sound natural. And of course my family just gotten used to it over time.

I first realized it with Dan. Occasionally he would talk to me in Chinese, but often without context and just stringing together verbs and nouns. I get it, I can’t be bothered with grammar most times either, but it made it really hard to understand him. When I did understand, it just felt awkward. I couldn’t put my finger on why for the longest time, but more importantly I didn’t know how to correct it.

Once I realized it was because we were both translating English answers to Chinese, it felt like night and day.

I started paying attention to native speakers at the food court, stores, tv shows, anywhere I could casually (and politely?) eavesdrop. It wasn’t hard to spot out because I could naturally understand it, not to mention say it. I just wasn’t used to thinking like that. It became another memorization exercise, where I would jot down natural sounding phrases and responses.

I’m hoping to start a new series, speak and think like a native. The intention will be to share my journey and findings of how native Chinese speakers communicate.

It’s a bit laughable that a non-native speaker is writing this, but I think that’s where I can spot differences and explain it a bit more - something a native speaker might not even realize they’re doing. I’m relying a lot on the questions I get from Dan, as well as my own mistakes. Thankfully my Chinese teacher is very patient.

So without further ado.

The Scene:

Dan and I are finishing up a card game. We don’t have enough time to start a new one before dinner, so he says.

Bad, Translated Chinese:

玩完了 (wan2 wan2 le5), which directly means “done playing” but really indicates “game over.” Something final and completely, indisputably over. I’m not trying too hard here because, well first off don’t learn this as I’m pretty sure he said that because he thought it was fun to say “wan2wan2”. He’s like that.

See what I mean about the short noun and verb pairings. Oh, and while this time I understood him, I still couldn’t help but roll my eyes a bit. I think my face ended up like a cross between 😯and 🤨…which probably meant I looked like 🤭or even 😬. I’m trying to be encouraging though.

Good, Native Chinese:

So other, better ways to respond in this scenario would have been:

- 玩很久了,不玩了(wan2 hen3 jiu3 le5, bu5 wan2 le5), which translates to “We’ve been playing a long time, let’s stop playing.”

- 玩累了,不玩了(wan2 lei4 le5, bu5 wan2 le5), which translates to “I’m tired, let’s stop playing.”

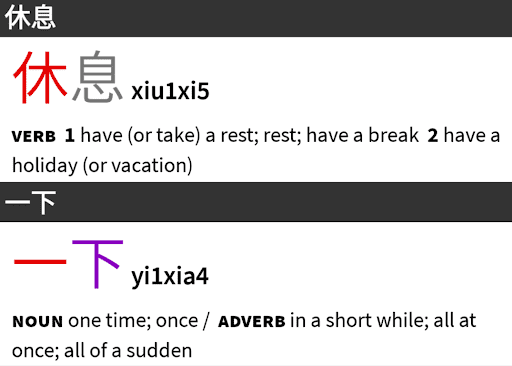

- 休息一下吧(xiu1xi5 yi1xia4 ba5), which translates to “Let’s take a short break” and implies that we should stop playing.

Since these are phrases, that don’t come out cleanly in my dictionary. However, I thought this was still worth noting.

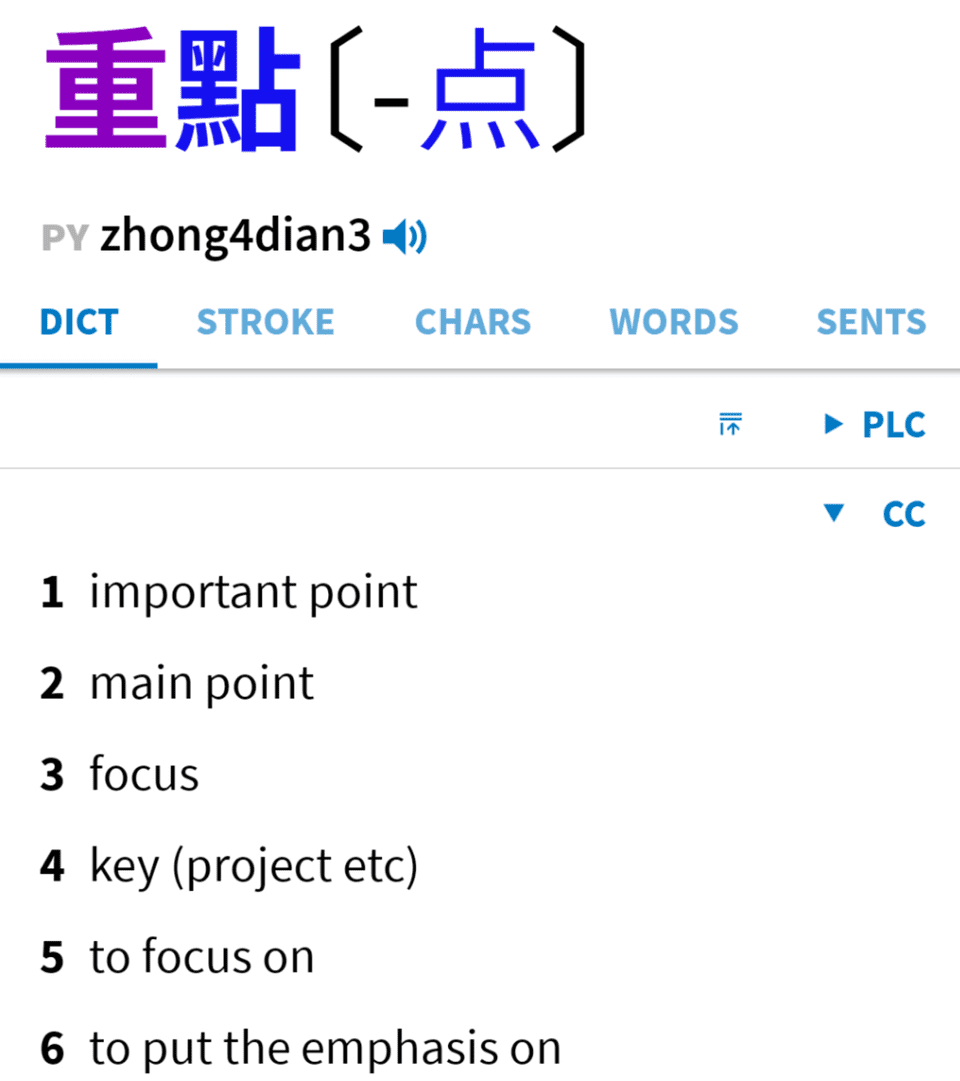

Of course the 重點(zhong4dian3), or important point, is 不玩了(bu5 wan2 le5). But unlike in English, where “Let’s stop playing” can seem fine, hearing just that in Chinese felt abrupt. It feels more natural to add a bit of context, like we’ve been playing for a while so I’m tired and want to take a break.

Let me know what you think, or if there are any other questions I can dig into.