The Mind is a simple card game that’s surprisingly addictive considering it only takes 5 minutes to explain. Gameplay lasts anywhere from a few minutes to a half hour. You can read the full rules here, but it’s essentially the card version of the ice breaker where you order yourselves in a line from youngest to oldest. But with cards numbered 1 to 100 (you get n cards in level n, and n+1 cards in level n+1). And remember, no talking.

Here’s Dan and I successfully passing Level 5 with both of us placing, in the correct order, cards 4, 10, 14, 45, 47, 54, 62, 69, 70, 71.

There’s several ways this co-operative game helps you learn to work together. Since you can’t talk, you learn to watch for the slightest body movement. The eyes are a given, but then you start noticing people hedge. You shouldn’t ignore it, after all, that card might be lower than yours. You learn to weigh your own decision against that of the team. Together, sink or swim. I see this naturally building empathy among coworkers. Did you notice them begin to speak up in a meeting, but then stop because somebody else spoke up first? How about with your remote or not co-located teammates? Our body language speaks a lot louder than what we actually say.

The next level adds another card. So in the example above, Dan and I each had five cards in Level 5, but when we moved to Level 6 we each had six cards for a total of twelve cards.

While we shuffled the cards, we inevitably started talking, strategizing, and sometimes apologizing. ”Why didn’t you put the card down faster?!” slowly changed to ”Sorry, I should’ve waited when I saw you start to put your card down.” Blaming each other doesn’t really work because what do you really win if you’re “right,” if that’s even possible? Right or wrong, if you fail as a team, in this game you fail individually. And inevitably, you start making tiny concessions and agreements with each other. And you try again.

When we played in a larger group, I couldn’t help but be reminded of an agile retrospective. After all, the point is to get the team to reflect on what they should stop, start, or continue doing. And this repeats every iteration. It takes a few levels, but eventually the team gets to a good rhythm and the “stop doings” become “continue doing”.

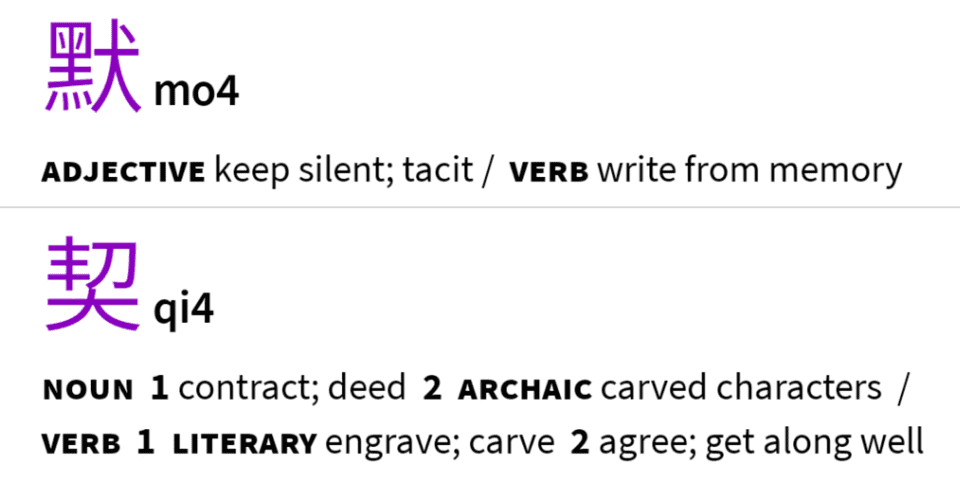

An added benefit that I was not expecting was being able to play this game across different cultures. The language barrier frankly did not exist since everybody can count to 100. And since there’s no talking, Dan was able to play with both my parents and my sister-in-law’s family. While they couldn’t really strategize between rounds, they all agreed afterwards that it wasn’t really necessary to achieve this 默契 (mo4qi4). In Chinese, this tacit understanding comes after you’ve connected at a very deep level with each other. You can see individually how these words lead to that since 默 (mo4) means tacit and 契 (qi4) means agreement.

All in all, for $15, I love how this simple game was so playable across so many perceived barriers (age, language, even interest in games). It highlights how even a random group of people, young or old, American or Chinese, can form a team. And best of all, nothing can really compare to the bond and immense satisfaction you get when you start thinking, playing, and succeeding as one mind.